By Chris Caswell, Sea, June 1976, pp. 44 - 47.

Hale Field modestly overlooks the fact that he helped Willard design the Vega-30s, and that he'd designed the Vega-40 hull.

Perhaps the title Boat & Owner is a misnomer in this case, since it would be far more accurate to say Boats & Owner. The name Hale Field as well as his yachts (Renegade, Fram, Hawk) are woven into the tapestry of West Coast yachting and to pick one name out is a slight to the rest. In the course of a lifetime around the water, Field has circumnavigated the North American continent, commissioned the design of a well-known motorsailer, designed several boats himself, abetted the rebirth of a traditional design, and is now building yet another boat.

"In 1950, we'd had our children and we thought it would be nice to have a boat again. I got together with Lyle Hess, a really good designer, and we thought that a boat based on actual working use would be nice. So we cast about and found the old Itchen Ferry cutters of England. Of course they were fishing boats developed to carry a load of fish but they had to sail well because they had no power. Eventually the gentlemen of the day saw they were good sailing boats and started racing them.

"We developed some lines and I came up with a sailplan that was reflective of the old cutters. We gaff-rigged her to be traditional and also so you could pull the topsail down at the first reef."' Launched as Renegade in 1950, she had single sawn frames of hackmatack every third frame. As a result, she's kept her shape after 26 years, although a lot of the credit goes to Lyle and Roy Barto who built her.

Renegade, still sailing in Southern California, is a traditional cutter, 24½ feet on deck. Larry and Lyn Pardey saw her, liked her lines, and built a sister ship which, named Serrafyn, is famous for cruising. Except for some materials and for a marconi rig rather than a gaff, the two vessels are identical. "We sailed Renegade for a while and, in 1954, I modified the rig by adding a topmast to get more sail area for the light airs of Newport. We entered the Ensenada Race and, by golly, took first overall in PHRF. PHRF wasn't the full blooded affair that it is now, so we had Renegade measured to the old CCA ocean racing rule and took CCA overall in Ensenada in 1957. I'm pretty proud of that, since we're the only vessel to ever win both the President of Mexico and the President of the U.S. trophies."

Field tried a lot of things on Renegade: sailed her like a bawley boat without a boom, and sailed her for a year without an engine. "We sailed in and out of everywhere, although sometimes she'd leave you out waiting for wind. But there's a great deal of pleasure out there at night if you're not frustrated. If you're not in a rush all the time, you can really enjoy it and you'd be surprised at the progress you can almost always make."

Field kept Renegade until 1962, when he switched to a brand-new Cal-28 being produced by his friend Jack Jensen. "Boy, that was a transition! Going from a solid wood boat to a Tupperware dish was hard, but the worst thing was the change from having a steady helm to one where the boat would turn around if you looked away. But it was a lot of fun because every new Jensen boat did well, and we were the first Cal-28 to start racing."

Hale Field is a gentleman in the classic sense ... considerate, quiet, self-effacing. You can't image him ever having to bluster about his accomplishments, although the stories and tales roll forth without ego. It's not difficult to see why so many yachtsmen are delighted to call him a friend.

"About 1964, I again found that I could manage to do some cruising. My training was as an engineer, but I got into real estate investments in the Fifties which allowed me to arrange my time. So I got together with another designer-friend, Bill Lapworth, and he came up with some plans to meet my specifications. I wanted the biggest boat that my wife and I could handle by ourselves, enough space to live aboard, good sailing ability, and enough power plant to go upwind.

"I shopped all over the world for a builder, came home, and found that Willard right here in Costa Mesa was between projects. They turned out to be great ... 'course the boat cost money but, at the same time, everything I paid for went into it."

It was Willard's concept to build the 46-footer by making a one-off female mold instead of the more conventional method of laying glass over a male plug and then finishing the exterior. The female mold required planking in reverse, "we had to think backwards all the time," but it permitted the very hard sprayed gelcoat which remains in good condition twelve years later.

Field named her Fram after the boat used by the explorer Nansen, and the name means onward in Norwegian. And that is exactly what Field did with her. Launched in mid-1965, Hale and Gingerlee Field moved aboard in 1967 as their four youngsters left home for college. Even their shakedown cruises were long by conventional standards; San Francisco and return, and then as far as British Columbia the following year.

But 1967 marked the great departure. Business again arranged, Field left in February and sailed down the coast of Mexico. "Fram was designed as a long-shore cruiser rather than a long-distance vessel, so we planned our runs for two days and one night between ports. It's more fun that way and, if you're not in a hurry, why hurry?"

After cove-hopping Mexico and Central America, they ducked through the Panama Canal, up into the Caribbean to Jamaica and the Windward Passage, and then over to Florida. "At that point, we did a thing that I'd just love to do again ... we sort of went with the boats that migrate like birds up and down the Intracoastal Waterway. The kids came and went as they pleased, and it was just delightful. We spent two seasons on the Waterway. In 1967, we went north and watched the America's Cup, up Lake Champlain to Expo '67, and then back down to the Bahamas for the winter.

"The following year, we went north early and that time we just kept going and wound up in Halifax, Nova Scotia. At that point, we decided that the best way to come back to California was to break new ground and so we planned to head through the St. Lawrence River and go down the Mississippi.

"But we took our time going along, and it got pretty late in the year. That was 1968 and there was a lot of unrest in the South ... people getting shot and so forth ... and there were some lonesome stretches of the Mississippi. We weren't scared, but it wasn't fun either."

Hale Field is one of those people who seem to acquire friends along the way like other people collect match books or hotel towels. One fellow he met, the owner of a small railroad near Sault Ste. Marie, said he could get Fram onto a flat car bound for Vancouver. The end result was that they activated a pair of huge locomotive wrecking cranes to lift Fram's 17 tons like a dinghy on davits. 'The overhang on the sides wasn't bad, but the critical dimensions were the upper corners where they might hit bridges or tunnels. The railroad made an accurate profile of Fram and matched it to their overlays of every obstruction on the whole route to make sure we'd fit."

Arriving in Vancouver, Hale Field was prepared for problems after the fuss over on-loading Fram's weight and bulk. But the yard boss didn't seem too worried even when Field kept emphasizing the 34,000 pound load. "When the boat arrived, they just called up a regular rubber-tired crane, picked us up like a toy boat, and placed us in the water. They were used to really big loads."

They moved aboard in Vancouver and started south. "I guess we could have learned it from the pilot books, but the wind on that coast blows from the south in the winter. Storms come from the south and clear from the south. It wasn't much fun." So Fram wintered in Seattle and completed her circumnavigation of North America in 1969.

Field smiles as he recalls the voyage, "I think the best thing about the two seasons on the Intracoastal Waterway is the sense of purpose. Around Southern California, once you get to Catalina people say 'what'll we do now?' On the Waterway, the what'll we do now is you'll make your next port. And it's all stretched out in front of you, which gives you a theme for your cruise. There's an on-going feeling about cruising that I found very pleasant.

"It also gives your crew an objective that is more than just getting someplace to drop the hook and have cocktails. Especially with young people, who have more energy and want to do more. They get tired of just going from A to B on a whim, but if they understand that there is an objective, then they're happy."

Fram was designed and built so that the two Fields could handle her easily. "Of course, if you were going upwind, you were powered. We powered a lot too ... with the engine aft and the inside pilothouse forward it was quiet and easy. On autopilot, you'd stand your watch in socks and a light sweater and read a good book, looking up occasionally to check outside."

When Field was looking for a builder, he'd contacted Jack Jensen to see if he'd be interested. But he wasn't at the time. "But once it was launched, he thought it was a pretty good boat and wanted one himself, and that's how Jensen Marine came to produce Fram as the Cal-46. They made about 14 with the same layout as mine. I still think the original 46 is a collector's item. When they modified it to the Cal 2-46, it became a Catalina boat and sold like hotcakes but they'd lost the inside steering and the ability to carry a skiff on deck."

Fram and the Fields made several more coastal cruises, including a two-year voyage as far north as Skagway, Alaska. "We set up two-week sections when we cruise and then invite people to pick a section when they would like to join us. If no one speaks for a certain section, then we'd go on our own. Otherwise we stuck to a comfortable schedule and people join and depart as we cruise along."

Does Hale Field do much racing? "Sure, but I don't think I could get much pleasure from spending all the money to win a race. The excuse to me for racing is to get out and see things that you can never see in normal boating. I've been sailing the Little Whitney this year with Bill Lapworth on his boat, and we've had some really beautiful and dramatic races, especially at night when you wouldn't be out otherwise. You know, you can't just invite people to go sail around Eagle Rock at midnight ... they wouldn't come. But, gosh, it was pretty." Here, again, is the pleasure of sailing with a theme. It may be a race, but you have to enjoy it as you go.

"I've never been much in favor of rating rules designing boats, which I think they clearly do. I don't think the sea has changed much and just because we change rating the rules shouldn't affect anything. Sailing boats have evolved over a long period of time, but some of the changes aren't improvements. I shoot towards a handy boat rather than a low rating. To me, if it takes five guys to sail a boat fast, then you don't necessarily want those same guys along on a pleasure sail. But if a boat can be handled easily by one or two people, then you can select the others for qualities besides being able to grind a winch."

Even in racing, Field has sailed with both good boats and good crews. TransPac in 1955 aboard Nam Sang, navigator with Don Ayres on Wild Turkey in the 1971 SORC, navigator with Bill Lapworth on Merrydown most recently. "In 1939, Peggy Slater, George Fleitz and I shipped our PICs up to San Francisco to race at the World's Fair, so my racing goes back a ways."

In 1971, Hale Field decided he wanted a bay launch for Newport Harbor so he could visit friends from his waterfront home. "There didn't seem to be much point in making a 5-knot boat that didn't sail. You can't go faster in the bay, so it might as well be a sailboat."

The result was Hawk, a pretty little schooner of 19 feet overall that Field built in his backyard. "She's just a big open cockpit bay launch with tanbark sails and a diesel engine, but we started getting ambitious and pretty soon we were going places with her. She's dry for her size, which means she's wet and you shouldn't go too far outside."

So Field the designer went to work again. "I've read a lot on naval architecture, worked and sailed with both Lyle Hess and Bill Lapworth, but I finally took the Westlawn correspondence course." He also modestly overlooks the fact that he helped Willard design the Vega-30s, and that he'd designed the Vega-40 hull.

"After Hawk, I started thinking about another boat something like

but big enough for a watertight cockpit and safe offshore. Besides, it's fun to build boats."

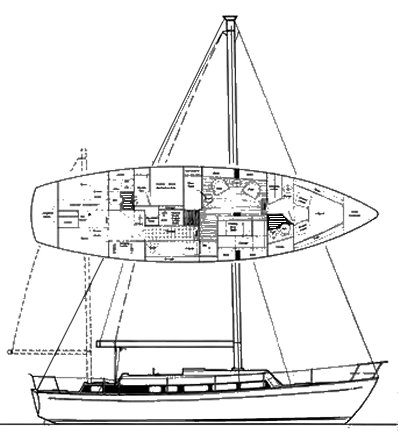

The newest Field creation is still just a glossy white hull sitting in the Willard shed, but she'll be a 31-foot schooner when finished. "I think of a schooner as a sloop with an area between the masts where you can deal with your extra sail area more handily than going out on the bow with a spinnaker. That's much better than pulling down one sail to put another up. Blondie Hasler (originator of the single-handed TransAtlantic race) once said that a boat where to get more sail you have to pull one down to put another up is like having a car without gears. When you get to a hill, you jack it up and put on smaller wheels. That's why I like the flexibility of a schooner rig. She sails just like a sloop, and you can fool around with the extra sails in the middle of the boat."

How soon is the new and un-named schooner due for the water? "Oh, I don't know really. I'd rather not aim too hard for completion date because I'm savoring the building process."

Like the building process and like his cruises and races, Hale Field has a theme to his life, but he always has time to enjoy the passing view.

Author: Chris Caswell, Sea, June 1976, pp. 44 - 47.